Alumni Programs is denoted as AP and Addison Houston is denoted as MT in this interview.

We invite you to join us as we sit down with environmental planner, equity and social justice advocate, and Climate Adaptation Strategist, Addison Houston to learn more about his story, journey at Evergreen, and how he is helping Washington State move toward equitable, climate resilient communities.

AP: Tell us about yourself, who is Addison Houston?

AH: My name is Addison Houston. I use he/him pronouns, I am a father and currently staffed as the climate adaptation strategist with Public Health – Seattle & King County’s Climate & Health Equity Initiative.

I went to Evergreen for my undergrad and then went on to California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo (Cal Poly) to receive my master’s in city and regional planning (MCRP) where I focused in environmental planning and hazard mitigation. I took one of my first jobs with the Bainbridge Island Metropolitan Parks and Recreation District and completed my master’s thesis work with them, investigating forest management practices following the history of heavy logging in the Pacific Northwest and its relation to wildfire risk in the wildland-urban interface. On Bainbridge, a large part of the current forest is comprised of monocrop species that were planted for the purposes of continued logging. This has resulted in root rot and disease spreading through their forests. With increased development of properties next to these forested areas, there has been an increased concern of wildfire risk. Upon graduating from Cal Poly, I took a job with the Washington State Department of Ecology in their Water Quality Program, where I served as a general permit coordinator for the issuance of general permits under the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) program of the Clean Water Act.

After a year of working with the Department of Ecology, I became a dispirited after realizing my job was serving to protect industry more than the environment. So, I decided to make a change and went on to work with the Hawaii State Department of Health as an Emergency Operations Center (EOC) Coordinator. When I accepted that job, I had some familiarity with the field of emergency management from my work in grad school on hazards mitigation, but had no idea about public health, so I ended up googling it!

The program in Hawaii I worked with was part of a national program called the Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) and Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP). Funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the program was formed after the events of 9/11 and initially focused on bioterrorism response and prevention, but after Hurricane Katrina, the program was amended to enabled public health to adopt an all-hazards framework. Expanding the role of public health to assess any type of disaster and its impact to peoples’ health, and increasing public health’s capacity to respond to any type of disaster or major emergency to address directed and indirect impacts - which occur when people are exposed to post-disaster conditions.

Going out to Hawaii was a huge amplifying event for my career, throwing me well outside of my comfort zone. When I started with their PHEP program, there were escalating tensions with North Korea around their use of nuclear missiles. And given how militarized the state of Hawaii is, we were doing lot of preparation for nuclear impact response. Now, I have way too much knowledge on nuclear response and survival – but those efforts were ended abruptly when a false inbound nuclear missile text alert went out across the state causing mass hysteria and panic.

When I started with the Hawaii State Department of Health's Office of Public Health Preparedness, the supervising position above me was vacant. So, after a year I decided to apply, and I became their Senior Planner. There is a saying of ‘trial by fire’, and the day I assumed that role was the day the Kilauea East Rift Zone (KERZ) eruption on the Big Island began and I was thrust into figuring out how to respond to a major volcanic eruption. We worked on deploying air quality monitoring stations to detect harmful gasses being emitted, sending out notices to the public and first responders, ensuring there was access to clean drinking water, and assessing occupation hazards for those working out in the field. Immediately following the KERZ eruption, there were two major hurricanes that came barreling through. One of which, Hurricane Lane, was recorded as a category 5 hurricane that came within 12 hours of impact of Honolulu. I remember evacuating my home and looking out over Honolulu as we made our way to the west side of the island to a more protected area, and it looked like a black mass just spinning out over the entire horizon, it was one of the most eerie scenes I have ever witnessed. Fortunately, the storm dissipated before making landfall.

After going through that my wife and I recognized that being out in the middle of the Pacific wasn’t a place we wanted to be when a hurricane does hit and wanted to be closer to family, so we looked at moving back to the West Coast. I was eventually offered a position with Public Health – Seattle & King County as an environmental health emergency response planner, where I focus on post-disaster environmental health needs. I have held this position now going on 5 years, and this past May I assumed my current position as a Climate Adaption Strategist, while continuing my role as the department’s environmental health emergency response planner – just with an increased focus on climate hazards.

AP: What brought you to Evergreen?

AH: In high school I participated in the running-start program and received my associates in arts degree and my high school diploma at the same time. Back then I wasn’t the most academically oriented and the expectation of my family was going to college after high school and not taking a gap year. So, I went out to the University of Hawaii at Manoa to pursue a degree in wildlife zoology. At one point, it was a career path I thought would be interesting and would allow me to be out in the field and not stuck behind a desk. But when I was at UH - Manoa the wildlife zoology program at the time received significant budget cuts, and the program was going to take me 5 years to complete due to limited course offerings instead of the 2 years I had planned on. At the time, while living in Hawaii I also had the opportunity to work at the local zoo in the African savannah mammal section where I got to work with giraffes, zebras, a white rhino, and a couple of ostriches. It was a very eye-opening experience, but I began to realize that I didn’t want to pursue that work and found I had a bit of an ethical and moral dilemma around zoos and how animals were displayed.

While in school, I realized that in the college environment of a 300-person lecture hall it can be easy to go unnoticed and got into a bit of a bad habit of not attending classes and just showing up for the test. I found myself preferring to spend my time surfing, working, and just hanging out at the beach – because it was Hawaii. I did okay and was able to keep up my grades, but it didn’t feel like I was getting much out of it. So, I decided midway through the first year that it wasn’t for me and opted to drop out with the intention of reenrolling at Humboldt State University, which was renowned for its marine biology program. But during that period, I did lots of self-reflection, finding out what I wanted to do with my life, and I didn’t feel like I was ready to take academics seriously, so I took time off to focus on myself.

During that time, I did a hitchhiking trip across the American Southwest and had exposure to a lot of people doing different things, visiting friends at different colleges and listening to their experiences. When I returned to Washington State, I joined a help exchange program in Sedro-Wolly outside of Bellingham. It was there that I learned one of my housemates had graduated from Evergreen and learned more about their programs. I knew Evergreen was a progressive liberal arts school, but I had never really talked to someone who had graduated, I learned how Evergreen helped them with their career and put them on the path they wanted to pursue. That’s when I made the decision to apply to Evergreen and pursue an independent major in human ecology, working to understand the interaction between different cultures, societies, and their interactions with their environments. Exploring historically how different society's interactions with their environments contributed to either their success or their demise.

When I went to Evergreen, I did a lot of independent learning courses (ILCs) to complete my degree and graduated in 2013. And it illuminated how being in the right place at the right time can open doors for you, doors you didn’t even know existed.

AP: Were there any classes or faculty that inspired you while at Evergreen?

AH: Yeah absolutely, when I first started, I took Mind, Body, Medicine with Mukti Khanna and I had a great relation with her. She was also my faculty advisor for several ILCs that I took at Evergreen, my ILC’s focused on bio-cultural ecology approaches, she was so receptive and accepting of the learning I wanted to do. When you investigate the interaction of different cultures and environments there are cultural belief systems that affect that, so part of my work entailed investigating the spiritual and world-belief aspects of various cultures and how they played into their interactions with their environments. Mukti was always very supportive of my work, you can't always cultivate a perspective that incorporates cultural belief systems and spiritual traditions into the study of ecology in a traditional classroom setting.

There was also Steve Abercrombie and Al Josephy, who taught the course Ecology and the Built Environment. That class introduced me to the field of city and regional planning which set the stage for my graduate studies at Cal Poly. They gave me a window of insight showing me how I could integrate and apply everything I was learning into something I wanted to do, and I could finally envision my future.

I also must extend my appreciation for Aisha Harrison, my ceramics professor. In my final year at Evergreen, I had done so many ILCs working with Mukti that she told me to take advantage of the facilities and resources Evergreen has to offer. That final year I took several art classes and ceramics was one of them. It really is a disservice for traditional colleges where students are forced into a path of required electives and core classes that don’t allow students to also pursue arts and creative practices. Evergreen gave me a better understanding of my own self-identity and creative aspects I wouldn’t have had a chance to uncover. Aisha was also the first faculty member I interacted with who I felt actually saw me. I had struggled with my identity being bi-racial, always trying to align with parts of my identity while rejecting others. Aisha had the strong grounding and acceptance of multiculturalism. Openly claiming her identity and not feeling the need to fit into a bucket here or there, but actively claiming and owning her identity. I learned from her how to not feel shame from my identity, but to celebrate it and step into my whole myself.

AP: Can you tell us more about your role working as a Climate Adaptation Strategist for Public Health – Seattle & King County?

AH: Working as a climate adaptation strategist I look at different ways climate change is going to affect our environment and public health. Whether it's more heat waves, drought, heavy precipitation or rainfall events, or increasing frequency of smoke and wildfire events, my role is to investigate the health impacts that come from these events and identify ways we can protect public health to reduce population exposure and vulnerability to climate impacts.

We strategize on how we can reduce the health impacts of climate change through development of recommendations that work to reduce public harm and distribution of resources in communities where needs are greatest, like DIY box fan air filtration kits to reduce residents' exposure to the health impacts of poor air quality during wildfire smoke events. While addressing exiting environmental health disparities in communities that increase their vulnerability to the impacts of climate change like flooding, fires, smoke episodes, rain, and heat.

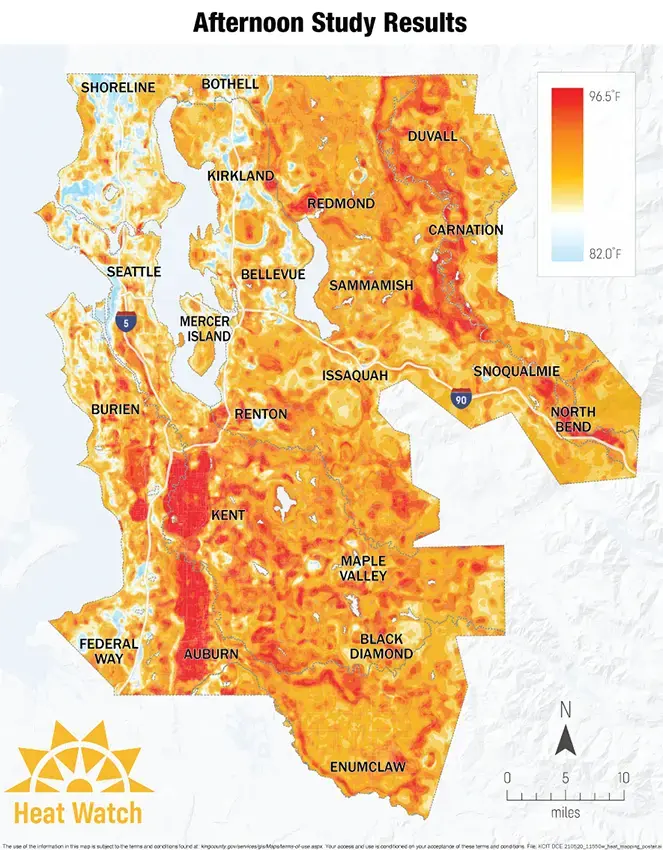

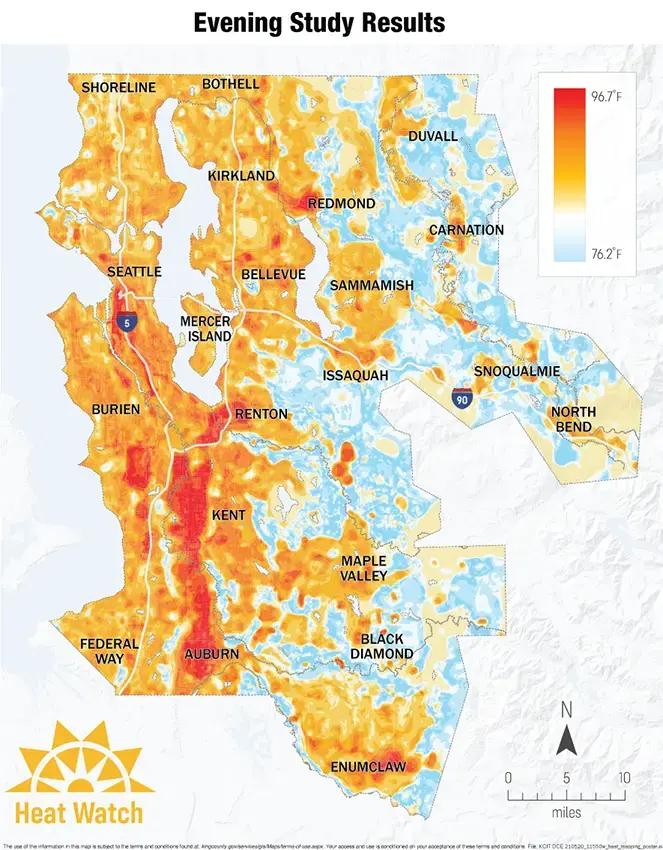

For instance, in a heatwave you need air conditioning to stay cool, but not everyone has access or can afford it, so we try to address how we can make access to these resources more equitable or identify effective alternatives that are more accessible when developing recommendations. We also work on identifying long-term risk reduction measures associated with changes that are necessary in our built environment to help communities adapt to the increasing risks associated with climate hazards, such as building code changes to address indoor air quality and filtration needs, mitigation measures to reduce the urban heat-island effect, and other actions intended to help communities adapt and cope with a changing climate and environmental conditions.

AP: How do you define equity?

AH: It’s a term that’s used a lot now that has become a bit of a buzz word, but how I define equity is self-determinacy; do people have the ability to make self-informed self-determined decisions about their own lives? Do people have the ability to control the risks they will be exposed to? Most people can't make that decision due to economic constraints, like housing for example. In our society there is an unspoken agreement that if you can afford resources, you can take preventive actions that can protect your health. If not, you are left to face the consequences. The risks people take on from a public health standpoint therefore end up being determined by their ability to access health promoting resources. However, there are existing disparities that affect people’s ability to access these resources – whether its healthcare, housing, air conditioning, air filtration, transportation, or even food – to increase equity we need to address these access disparities and the root causes as to why these disparities exist in the first place.

For example, the affordability of housing should not have a direct correlation with the quality of housing. When the expectation is that people must pay more to have a healthier home environment, it is directly contributing to inequity as people unable to afford the premium we place on heath are often relegated to a substandard housing situation where individuals face a larger range of health risks they are exposed to. Location plays a huge role in this too. It comes down to the exposure of different risks in people’s environments like industrial emissions sources, and proximity to resources like food. There are food deserts where some communities only have access to convenience stores carrying low quality processed foods and maybe not a grocery store with fresh produce and whole food options.

In public health, equity is about understanding the cumulative risks people are subject to and addressing where disparities exist in the ability of individuals to take action to reduce their risk. It requires understanding the upstream drivers and root causes that need to be addressed to increase the ability of self-determinacy for people to be able to make their own decisions on what health risks they are willing to take on. So, to me equity is about self-determination and the freedom of choice in a manner that is not prescribed because of who you are or where you live.

AP: What is the biggest challenge we face to achieve equitable, climate resilient communities here in Washington?

AH: Follow the money. We need to invest in capital improvements and infrastructure to reduce the disparities in our communities and reduce harm. We need to help the communities that are on the frontlines of disasters, so they are well equipped. If you have the luxury of air conditioning, then a extreme heat event won't impact you as much as someone who can't afford a/c or someone who experiences homelessness. There needs to be a willingness to make more committed investments about the quality and condition of our built environment.

But funding is a major challenge and when it comes to climate change, we are already seeing its impact. Within Washington there are a lot of investments going into greenhouse gases which illuminates our commitment to reducing the amount of climate change we experience, but we also need to recognize that the impacts are already occurring. And these events are inflicting different levels of harm on our communities based on people’s ability to access the resources necessary to protect their health. If we want to level the playing field, we need to invest in those who historically have been overburdened by environmental injustice and may not have access to resources necessary to protect their health without external intervention.

We must think beyond what’s happening now, and start accounting for changing hazards people will face, and we need to think about the future displacements of communities who will be displaced by climate events. We need to ensure that future generations and people like my daughter can still enjoy the world in 20-30-50 years and at minimum have the same opportunities we do. She is only 16 months old now, but already that future is uncertain. But we must act now and make what decisions we can because many of the changes that are needed will take us years to accomplish, and our window of opportunity is closing.

AP: Who opened doors for you?

AH: A lot of people have opened doors for me, but it wasn’t necessarily because I had connections with those people. Growing up bi-racial I had to prove I belonged, and growing up in an affluent area with limited diversity there was almost an expectation that I would never be able to amount to the same potential as my peers. However, from a very young age my parents instilled in me that I was going to have to show up and prove I belong no matter what endeavor I pursued. So, I have carried myself knowing I have to demonstrate I belong no matter where I am. So, showing up with that pre-understanding seems to have resulted in a tendency of people leaving the door open for me when I showed up. It's hasn’t really been a matter of who opened the door but the dedication that I put in to prove that I belong, and people became receptive to that and left doors open, which has been huge for me.

I can't explain how I got into the work I do now because I never tried to pursue this path, I showed up in places and people were willing to have a conversation with me and opened the doors to so many opportunities. If you asked me 15 or 20 years ago when I was in high school, I would not have anticipated I would be where I am now. It comes down to personal drive and perseverance so you can display you are in the right place no matter where you are. If someone does present an opportunity and opens a door for you, and you haven't put in the forethought or work, the doors can close fast. You need to be ready to meet the challenge and rise to the occasion when you are presented with opportunities.

One thing I’ve always carried with me from my participation in youth sports is that who wins a game isn’t determined by the game. It’s a matter of who put in the practice ahead of time and knowing you’ve practiced more than the other team, that’s how you win, that is how you succeed.

AP: What impact do you hope to make through your work?

AH: Being able to help reduce the disparities from climate impacts that results in some communities being affected more than others, and increasing accessibility to resources that can help protect people's health.

Making it so we can adapt to a changing world, not stuck in a reactive stance, by taking proactive measures. We have so many opportunities to construct and conduct our society in a way that promotes the ability for everyone to achieve their potential, there is so much potential, but we need to be proactive about it and take advantage of the opportunities we have now; reacting to things as they occur will be too late. We can be reactive and face more challenges but if we are proactive, we can take advantage of the opportunities.

AP: What advice would you give current students studying at Evergreen today who will join you as alumni?

AH: You don’t have to wander a straight path, and you don’t always have to know where you are going. It's okay to wander. I would also say think differently, but don’t be afraid to talk to others who think differently from you. We are all in this together and open dialogue will help us find common ground. Accepting differences will make us stronger and finding commonalities that we can leverage can help us obtain an understanding greater than any single viewpoint.

AP: What is your superpower?

AH: I had to think about this one quite a bit! I think what stood out to me is the notion of clairvoyance, not being able to see the future but perceiving things beyond what could be. I have always been good at holding contrasting and conflicting viewpoints which in part comes from being bi-racial. I’ve always had a systems-oriented perception. Allowing me to see how different things interact and influence each other, recognizing patterns and outcomes that are likely to occur because of certain conditions are present. It has allowed me to perceive things in a way others might not see before things happen. Which fits with my role, anticipating impacts we’ll likely see as a result of climate change and how we can prepare our communities, so we are not in that reactive mindset.