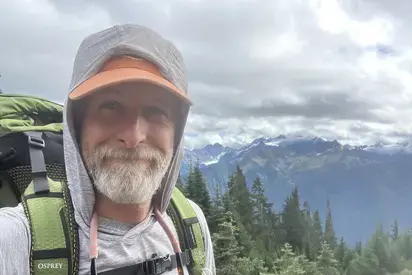

Marine biologist John Calambokidis '78 is a leading expert on whales and a co-founder of the Cascadia Research Collective.

This summer, marine biologist John Calambokidis ’78 heads south from Olympia to the Southern California Bight to conduct six weeks of fieldwork, much of it aboard an 18-foot rigid-hull inflatable boat as far as 50 miles out on the high seas. He’ll be collecting data on the abundance of marine mammals off the US West Coast, including some of the Navy ranges off southern California where submarine-detecting sonar signals are heavily employed during military exercises.

The work on Navy sonar will be conducted by a small flotilla carrying research partners who’ve collaborated for four seasons on the project. Together, they'll continue investigating how the underwater noise impacts the animals. This will provide a better scientific basis for minimizing its harmful effects, which have included strandings on beaches around the world.

Calambokidis will spend another three weeks in several of the West Coast’s busiest maritime shipping lanes, into San Francisco Bay and the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles, where he’ll resume his work to understand large vessel collisions with whales so solutions can be developed to avert the accidents. In recent years, ship strikes have become a major cause of death among whales worldwide. Many of the fatalities are endangered blue whales, the largest animals on Earth, but no match for the giant cargo ships, oil tankers, and cruise ships plowing through their habitat.

These two areas of research are current priorities for Calambokidis, who’s been studying marine mammals since he was a student at Evergreen. In the last of his three undergraduate research projects— all of which resulted in published papers— he served as the project director for a Student-Originated Study funded by the National Science Foundation to investigate the levels and impact of toxic PCBs in Puget Sound harbor seals.

Calambokidis didn’t start out with a passion for whales or other marine mammals. “Much more captivating was the ability to do research, go out and study and learn something unknown and make a discovery,” he said. “I fell in love with marine mammals later. My strongest pull was an interest in conservation and environmental protection, which translated into believing scientific research was an important way to promote conservation.”

To continue the harbor seal work he’d done at Evergreen, as well as the work of another student group studying the Nisqually Delta, Calambokidis and seven other alumni from the classes of 1975 to 1978 formed the Cascadia Research Collective in 1979 (including Jim Cubbage ’77, who still serves on the Cascadia board). Since then, the Olympia-based nonprofit, which has 23 employees, has dedicated itself to environmental research and education. Over the years, they’ve conducted hundreds of studies for government agencies and other nonprofits that need information to protect wildlife.

In 2013, Cascadia Research carried out 35 active projects ranging from the sonar and ship strike studies to its ongoing surveys of West Coast whales. Its three-decade-long photo-identification work, involving more than a dozen cetacean species, has amassed into an unparalleled catalog that allows scientists to recognize individual animals and aids other research. Calambokidis, who routinely photographs breaching whales when he’s at sea, has been called “the West Coast’s most prolific photo-identifier of whales.” He said the collection contains pictures of “in the neighborhood of 10,000 different individuals, including almost 3,000 blue whales.” The latter have been noteworthy because they’ve documented a population larger than previously estimated—although worldwide this species is still far below the number that existed before commercial whaling nearly wiped out the species.

Calambokidis’s work has taken him from the Puget Sound to the Alaskan and Central American waters of the Pacific Ocean, where he’s conducted studies on a variety of species, including once-common harbor porpoises, which have made a recent comeback in Washington. Mostly, though, he spends time off the West Coast studying blue whales, humpbacks, gray and fin whales, and the impacts humans have on these seafaring giants.

His shipping lane research contributed last year in changing the routes of ships traveling to California ports to steer them away from where whales congregate. “That’s the main mission I’ve been on that’s been effective,” said Calambokidis. “I’ve focused not only on doing the research to reduce ship strikes, but working with industry and government agencies to implement changes.” While the shifts are a good start in reducing the incidence of strikes, he says more still needs to be done, including slowing down the vessels. “Ships have gotten bigger, faster, and more numerous,” he said. Blue whales seem particularly susceptible to being killed and injured by collisions along the California coast, which Calambokidis worries might be one reason they haven’t recovered from whaling. “We’ve found they’re not adapted to avoiding the risk.”

Among his peers, Calambokidis is widely respected for his contributions to whale research and conservation. In 2012, they selected him to be the recipient of the American Cetacean Society’s John Heyning Award for Lifetime Achievement in Marine Mammalogy. He has coauthored two books on marine mammals: A Guide to Marine Mammals of Greater Puget Sound (Island Publishers), and with his marine biologist wife, Gretchen Steiger, Blue Whales (Voyageur Press). He’s published more than 150 papers in scientific journals and technical reports (a dozen in 2013 alone) and his work has been featured on the Discovery Channel, National Geographic, and in many other popular media outlets.

Calambokidis manifests his appreciation for his undergraduate education by maintaining a close relationship with Evergreen. He guest lectures at the college (and elsewhere) and periodically teaches a marine mammal biology class as an adjunct faculty member in the Master of Environmental Studies program. Cascadia Research has sponsored more than 100 Evergreen interns over the years.

After all, he said, “thanks to the latitude” he was given as a student, it was at Evergreen that he first experienced the thrill of research and discovery that continues to drive his quest to more fully understand the amazing creatures he has come to love.